The Internet makes talent communities inevitable

The Internet makes talent communities inevitable

In recent weeks we’ve seen a lot of outpouring of grief over the now dead SOPA legislation. The law’s critics claim that, if passed, the law would end the Internet as we know it, threaten our way of life, and confirm the Mayans were right. We periodically experience this type of mass hysteria, whenever something seems to threaten the “promise of the Internet” — the last time was over net neutrality. That so-called promise has to do with the perceived “free” flow of information: articles, stories, videos, songs, or content. What’s gotten lost in this noise is that that nothing is free. The current business model of the Internet has simply shifted dollars from content creators to content aggregators. Advertisers sponsor content so users can pretend it is “free.”

A long time ago, about the time the last ice age ended, there was something called AOL. It seems like eons have passed, but those who remember that era may recall that after we returned from foraging for food we would turn on our dial-up modems and connect to AOL, having paid a monthly fee for access to all the content that was available, the forums, the news, etc. Connection speeds were 1,200 bits per minute — you could almost count those bits coming in. Now we do the same with Facebook and Google, which we experience as free. Perceptually, we ignore the ads — targeted ads based on all the information collected by the sites — ads tailored to our habits, our behavior, and interactions. AOL charged a fee and had no ads; Facebook doesn’t charge a fee but has ads. There is no free lunch.

So now we have a business model on the Internet favoring networks that can attract members and keep them there. That requires having content that attracts users, however it may be generated. Initially, sites like YouTube and Facebook, with their user-generated content, left us wondering why they existed. But, they have been enormously successful and it is clear that communities naturally form where content gets developed and shared. The better the content a community brings to its members, the more of them it gets and the more engaged they are.

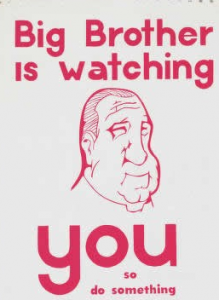

Big Brother is Watching You — and That’s OK

What we know now is that people prefer content they don’t have to pay for directly. We’re apparently willing to share substantial personal information with advertisers in exchange for “free” content. Just how much intrusiveness we’re willing to enable remains to be seen, but the boundaries are constantly being pushed — Google’s new privacy policy being only the latest example. The company will now offer a new “benefit” for users — it will track you across multiple services including Google+, YouTube, Gmail, and any other property they own, including Android phones. I wrote this on Google Docs, so what I wrote was likely being indexed as it was written. Big Brother was an amateur.

Imitation Is the Sincerest Form of Flattery

While users are opposed to paying for content (whether it is legally or illegally obtained), there’s an opportunity for employers. Any employer can create forums where content is produced targeting interests that are relevant to specific groups of people –- creating talent communities — thereby aggregating candidates they may eventually want to hire. This is the only way to create talent communities, built around a topic that candidates (or people that might become candidates) are passionate about: chemical engineering, pediatrics, Java, nursing, recruiting, etc. A place online where people congregate to share their interests and interact with each other. Anything else is not a community.

But this opportunity comes at a cost. Relying on Facebook or Google+ to create talent communities means accepting their terms of doing business. That is, giving them access to data that can be analyzed and sold to third-parties. That’s the price of “free” content. There’s really no getting away from it — the money to support Facebook has to come from somewhere. Although this model prevails today, there are other forces at work that will change the game. The exchange of personal information is at odds with our natural desire for privacy. So, as we continue to explore how much privacy we’re willing to exchange for “free” content on sites like Facebook, a desire for alternative models will grow. Other forms of sponsorship, where advertising is less apparent, will naturally appeal to those concerned with privacy, and may even serve to encourage community members to share more in a community with restricted membership.

Communities don’t have to be built entirely on Facebook’s terms. It is possible to create somewhat private communities. In fact, it is prudent to create communities on one’s own terms, rather than be at the mercy of a third party whose interests diverge from ours.

Employer-sponsored talent communities should be private domains for members that represent a group desired by the employer as employees. The basic formula for success is simple: develop or support the creation of content and make it available for free and accessible, and drive people to it. However, putting this into practice is a lot of work.

First, it requires having interesting content, which means that it needs to be material that is original, relevant to a particular group, and prompts controversy. Then there needs to be a critical mass of members in the community that gets engaged in robust discussion. That is what creates a community, it’s not just a repository of content. A community is one where people congregate to share their views and learn from each other. That’s the “social” part of social media, a fact that often gets forgotten in the zeal to build a lot of communities which are nothing more than databases.

This is what employers need to be doing today. There is no other way to create talent communities. But do it now, because who knows what’s coming that may make it difficult to create communities.