How familiar do the three scenarios below sound to you? They’re a few examples of how the siloes in talent management impact HR, employees, managers, candidates, and corporate executives. The impact: companies waste time and money; they compromise on the quality of their talent; their employee engagement deteriorates; and, ultimately, their business performance suffers. Breaking down these siloes is the topic of a workshop I’m running at the fall ERE Expo.

How familiar do the three scenarios below sound to you? They’re a few examples of how the siloes in talent management impact HR, employees, managers, candidates, and corporate executives. The impact: companies waste time and money; they compromise on the quality of their talent; their employee engagement deteriorates; and, ultimately, their business performance suffers. Breaking down these siloes is the topic of a workshop I’m running at the fall ERE Expo.

- Company X has a rigorous succession planning process, but the results of this process sit in binders in several HR business partners’ desks. Mary, a senior manager, has a critical vacancy, so she calls her recruiter, John, to fill it. John hires a retained search firm at great cost and expends a great deal of effort, but finally fills this critical but difficult-to-fill position. After the hire, John gets a call from his HR business partner, who asks, “Why were the three ready-now internal successors identified during talent reviews not even considered for this position?”

- Brad, a manufacturing site manager at Company Y, reviews his staffing needs on March 15 and determines that his plant is fully staffed. However, on March 22, he calls his recruiter, Jane, and tells her a change in business strategy has occurred, and he needs 100 new people at his plant by the end of April. Jane thinks, “Senior leadership must have known about this change three months ago. If only I had known ahead of time, I could have proactively pipelined external talent, and worked with Learning and Development and Succession Planning to pipeline internal talent. At this point, I’ll never be able to meet Brad’s timeline!”

- Peter, a new employee at Company Z, meets with his manager, Lisa, two weeks after his start date. In that meeting, Lisa tells Peter that HR requires every employee to have a development plan. She hands him a copy of the development plan template, and tells him to put anything he wants on it. Peter thinks, “I wish Lisa would give me more direction and support for my career development. I interviewed with so many people to get this job; you think they’d have some sense of my development areas and some suggestions for how to grow. I guess this company’s stated commitment to employee development is just lip service.”

Integrated Talent Management: the Solution

Many companies are trying to solve these issues by abandoning their siloed talent management models and replacing them with an integrated talent management function. But organizations are still struggling to understand what integrated talent management is.

An integrated talent management function has several distinguishing characteristics:

- Talent Strategy and Workforce Plan Are Tied to Corporate Strategy: An integrated function is meant to help the business meet the human capital needs of the corporate strategy. As a result, an explicit talent strategy and workforce plan are key to ensuring that talent management activities are aligned with the business. Workforce planning also allows an integrated function to rapidly adjust to changing business needs.

- Talent Management Processes Are Aligned to the Talent Strategy: The talent strategy and workforce plan should drive all talent management activities. In an integrated function, the talent strategy and workforce plan are the puppet-master, and the talent management processes are the marionettes.

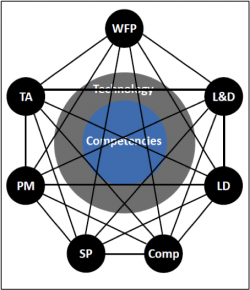

- Talent Management Processes Share Inputs and Outputs (see the graphic): This is a crucial piece of breaking down the siloes of talent management. All three of the examples of siloed behavior discussed above can be partly attributed to a lack of data sharing: Succession Planning not sharing bench successors with Talent Acquisition; Workforce Planning not sharing scenario-based hiring needs with Talent Acquisition, Learning & Development, and Succession Planning; Talent Acquisition not sharing hiring evaluations with Learning & Development.

- Competency Model as a Common Language: Each talent management process performs evaluations of talent. A consistent competency model ensures that each process can share that evaluative data with other processes by ensuring that those evaluations are using a common language. If talent acquisition is using a different competency model than Learning & Development, the value of hiring evaluations in the development planning process is greatly reduced.

- Technology Enablement for Talent Management: In some cases, the sharing of data across processes in Talent Management can be achieved without technology support, through cross-functional participation in meetings, or paper and email communication. However, technology support is critical to ensure these interfaces are scalable as a company grows.

- Change Management as a Foundation: The journey to integrated talent management is transformational, not incremental. A detailed and pervasive change management effort is absolutely essential to ensure that your business is able to follow your lead on that journey.

Creating an integrated talent management function is not just HR navel-gazing; it has been proven to have direct and measurable business results. According to the 2010 Bersin & Associates Talent Management Factbook, companies with strategy-driven integrated talent management functions have significant advantages over their siloed counterparts:

Creating an integrated talent management function is not just HR navel-gazing; it has been proven to have direct and measurable business results. According to the 2010 Bersin & Associates Talent Management Factbook, companies with strategy-driven integrated talent management functions have significant advantages over their siloed counterparts:

- 26% higher revenue per employee

- 28% less likely to have downsized during 2008 and 2009

- 40% lower turnover among high performers

- 17% lower overall voluntary turnover

- 87% greater ability to “hire the best people”

- 156% greater ability to “develop the best leaders”

- 92% greater ability to “respond to changing economic conditions”

- 144% greater ability to “plan for future workforce needs”

Integrated Talent Management: the Challenges

The benefits of integrated talent management are compelling, and the descriptions and diagrams above seem simple enough. So why don’t all companies have it? In the final analysis, most companies are struggling to develop a practical, simple, and systematic approach to designing their integrated function and determining a path to get there.

Consider this analogy. Assume that 300 engineers are tasked with designing a suspension bridge. In order to accomplish this, the group is split into three teams of 100 engineers: Team 1 is responsible for designing the towers; Team 2 is responsible for designing the cabling; and Team 3, the roadway. If this bridge were designed the way HR functions are designed, the head of the project would send all three of these teams to different locations, and simply say, “go.”

Once the team starts, Team 1 designs the towers, Team 2 designs the cabling, and Team 3 designs the roadway. But when all three pieces are put together, the bridge falls over. No one has taken the time to determine how the pieces fit together before beginning the design. The tower team doesn’t know what the cabling team expects of them in supporting the cables. The cabling team doesn’t know what the roadway team expects of them in supporting the road. And the roadway team doesn’t know how to design the road to fit into the towers.

So what is the antidote to this ill-fated bridge-building method? Come to my Fall ERE Expo pre-conference workshop to find out.