I was training a group of hiring managers in New York City a few weeks ago on the fine points of Performance-based Hiring. The conversation quickly focused to quality of hire: how to both measure and maximize it. One of the sales directors in the room was quite frustrated with his recruiting team, and suggested the way he controlled quality of hire was by rejecting 9 of 10 candidates their recruiters presented. The rest of the hiring managers then chimed by saying how disappointed they were with the quality of the candidates sent by their recruiters.

They attributed the primary cause to their recruiters’ lack of understanding of real job requirements. I suggested the problem was more likely a quality-control issue: using inspection at the end of the process to control quality of hire, rather than defining and controlling it at the beginning.

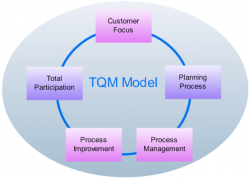

If you’re old enough to remember, back in the 1980s the Total Quality Management initiative became a global groundswell. This is turn spurred the growth of lean manufacturing, six sigma process control, and the Baldridge Award. The simple idea was that if you controlled quality at every step in the process, rather than reject the results at the end, overall costs would decline and quality would be maximized. The was the promise and essence of TQM and what its acknowledged leader, W. Edwards Deming, proposed. It worked, and led to a huge world-wide quality and productivity boom.

If you’re old enough to remember, back in the 1980s the Total Quality Management initiative became a global groundswell. This is turn spurred the growth of lean manufacturing, six sigma process control, and the Baldridge Award. The simple idea was that if you controlled quality at every step in the process, rather than reject the results at the end, overall costs would decline and quality would be maximized. The was the promise and essence of TQM and what its acknowledged leader, W. Edwards Deming, proposed. It worked, and led to a huge world-wide quality and productivity boom.

If you look around your business today you’ll see evidence of this concept in every function and business process, except for recruiting and hiring. Folks in HR and recruiting tried to implement these programs, but didn’t get too far. The underlying problem had to do with the lack of a meaningful and repeatable process for maximizing quality of hire. Without this, applying TQM-like controls is comparable to pushing on a cloud.

The problem for hiring has not yet been solved. Most companies still use a hiring process based on high-volume attraction and a quasi-scientific process for weeding out the weak, with the hope that a few good people remain at the end. A process based on how top people find and select opportunities might be a better place to start. With this in mind, here are some Deming-like TQM principles for building quality of hire into the system at the beginning rather than inspecting it out at the end.

- You need to have the strategy right before you create the right process. According to current #1 business-guru Michael Porter, strategy drives process, not the other way around. If you’re in a talent scarcity situation where the demand for talent is greater than the supply, you can’t use a talent surplus process. Here’s a recent post I did for LinkedIn describing this and offering a reasonable solution. If your company is still using traditional skills-infested job descriptions for advertising and using this flawed information to filter out people, you are assuming there is an excess supply of top people. If this assumption is incorrect, you need to rethink your strategy and bring your downstream processes into alignment.

- Define quality of hire before you start looking. The recruiter and hiring manager need to define and agree to quality of hire when the requisition is opened. This is not a job description listing skills and experiences. It’s not even adding more technical skills to the job description, or narrowing the criteria to top-tier schools and top-tier companies, or adding more IQ. Instead, it’s defining the actual work the new person needs to do in terms of exceptional performance. I refer to these as performance profiles. You can then use this criteria to filter and interview people based on their ability and motivation to do this type of work at the level of performance defined. Done properly, everyone seen by the hiring manager is then a potential hire. (Note: this is a huge TQM control point. See Point 5 below.)

- Build your sourcing and recruiting process around how top people look for new jobs and compare offers. Top people are not looking for lateral transfers; most find their next jobs through networking; few will formally apply before talking with the hiring manager; and they’re very concerned with the career opportunity, the challenge of the job, the impact they can make, and who they’ll be working for and with. Few companies build their core processes around the needs of these top people and then wonder why they can’t find them.

- Brand the job, not the company. After a few years in the workforce, top people are less concerned with the employer brand and more concerned with the actual career opportunity. Recruitment advertising should be written to instantly appeal to the intrinsic motivators of the ideal candidate. Very little of it does. Too many companies overspend on employer branding and not enough on creating custom and compelling job-specific career messaging. One size doesn’t fit all, especially as people mature and become more discerning career-wise.

- Use meaningful metrics like the “4 in 2” to control the process. Four hire-able candidates in two weeks is a pretty audacious goal for the recruiting department, but not an unreasonable one, especially with tools like LinkedIn and CareerBuilder’s Talent Network now available. If the first two candidates are off the mark, it’s an indicator something is wrong. If a hiring manager can’t decide whom to hire after seeing four candidates, rejecting them all, something is terribly wrong. Usually the job is poorly defined, sourcing is inadequate, or the interview and assessment process is flawed. Regardless, step back and figure out the problem before presenting more candidates.

Of course there’s more to maximizing quality of hire than described here, but if you don’t build quality in at the beginning of the process, you’ll never get it at the end. Desperation or normal business pressures will then force the hiring manager to hire the best person who applied, not the best person available. I address more of this in my new eBook The Essential Guide for Hiring & Getting Hired (January 2013). For now, consider that it took 30+ years for the U.S. to accept Deming and realize that building quality in at the beginning is a far better process than inspecting it out at the end. Let’s not waste another 30+ years to realize that the cost of quality of hire is free.