Artificial intelligence is advancing rapidly, and it’s already having a systematic, measurable impact on jobs. AI, and automation before it, have already assumed many of the physical and repetitive tasks, driving many workers from occupations such as farming, manufacturing, and mining. Meanwhile, people who remain in those industries are more skilled than the manual laborers before them because they need to collaborate with AI. In other words, the 20th century saw a shift from the Physical Economy to today’s Thinking Economy — whereby jobs moved from focusing on physical to thinking tasks.

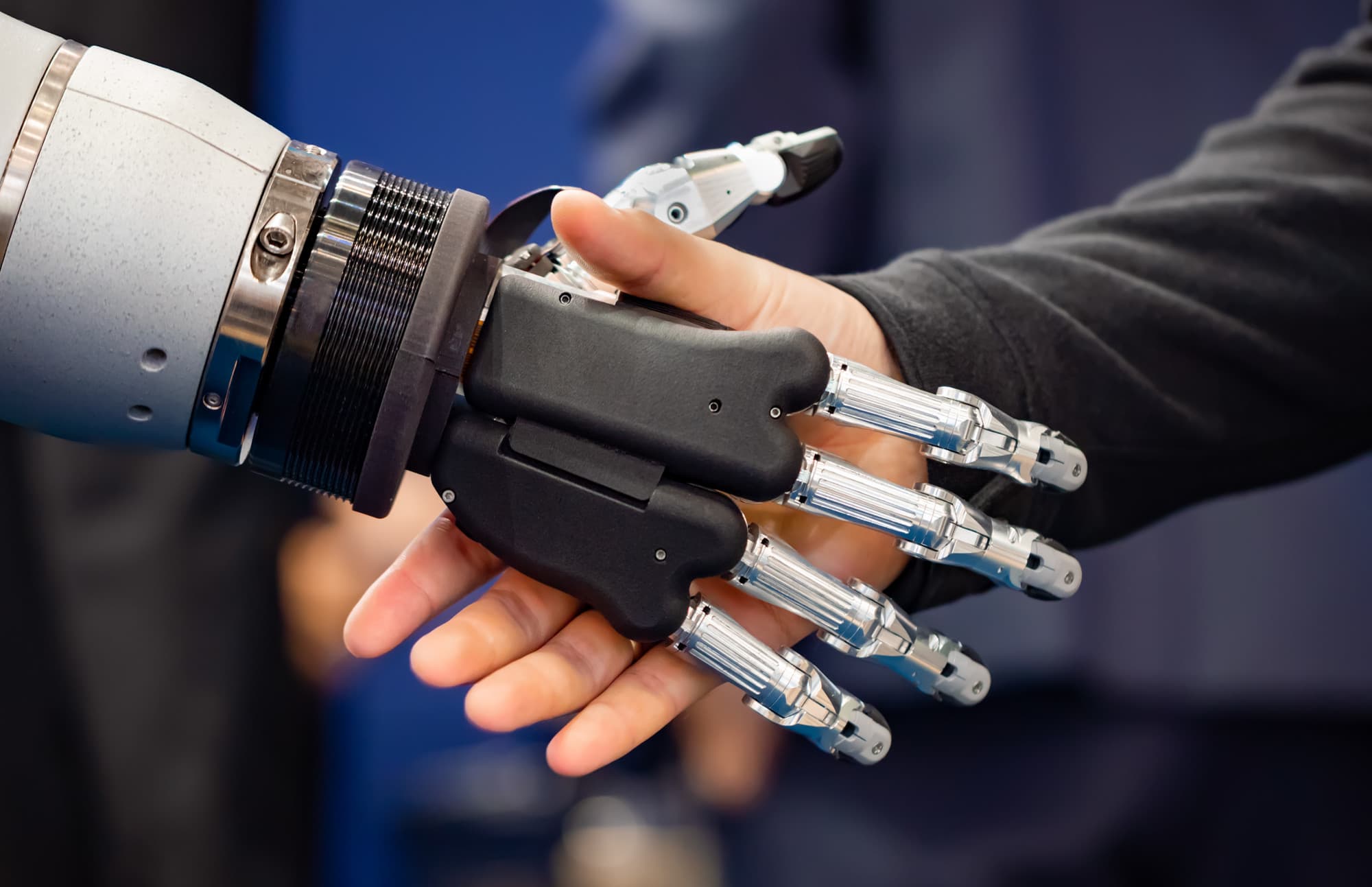

We are now in the midst of an equally profound shift as AI is taking on those thinking tasks. As a result, human workers now increasingly find their differential advantage over AI to be feeling skills, emotional intelligence, empathy, and interpersonal relationships.

For example, a financial analyst who used to spend significant time doing calculations now delegates such tasks to AI, which leaves more time for client contact. This, in turn, changes the required qualifications for the financial analyst job, with soft skills now assuming much more importance than mathematical ability.

These changes are not just taking place in highly technical fields. Consider, for instance, the game of baseball. The statistician Bill James popularized analytics in baseball, and today virtually every major-league team has a serious analytics group, using AI techniques to try to derive a competitive edge.

But surely the actual play of the game of baseball would not be affected by AI, right? Wrong! Baseball is now experimenting with robot umpires for calling balls and strikes, and the expectation is that an AI-based umpiring system will be implemented in the major leagues in the next few years (such robot umpires already exist in some minor leagues).

We can learn something from how robot umpires are employed. Rather than creating anthropomorphic robots that would stand behind the catcher looking like a stereotypical robot, the system is instead designed as a collaboration between AI and human intelligence. The AI system senses whether the pitch is a ball or a strike, and that information is communicated to the human umpire on the field, who is wearing an earbud. The human umpire then has the final say and can overrule calls that he or she feels are obviously mistaken.

The baseball example is instructive. The players and fans might not trust a fully robotic AI system, but with humans integrally involved, there is more trust. That is, the humans in the system seem to be necessary to establish the emotional connection and empathy that the people require.

We see similar instances in the field of medicine. In many cases, AI such as IBM’s Watson can do a better job than human doctors in diagnosing illness. The patients, however, trust the AI diagnosis less.

A human being, a doctor who can interact empathetically with patients is still needed. With a human doctor in the loop, the AI diagnosis can be done in the background, which makes the best use of both the AI and the physician. This means that the doctor must emphasize people skills more. What’s more, as this trend progresses, we will see that women, who are more empathetic on average than men, will comprise an increasing share of new doctors.

The above examples are only two of many that we currently see. By analyzing government job data, we find that feeling tasks — again, those that involve soft skills — are increasing in importance across the board, even in technical fields like statistics. This has profound implications for hiring. Organizations will find it wise to pay less attention to technical skills, such as STEM skills, and more attention to people skills.

This is true even in some of the world’s most AI-driven technical companies. For example, Google conducted an internal study to see which worker characteristics were most important for career success. They did this by comparing employees who rose in the company to those who were less successful. Out of a long list of employee characteristics, which included both hard and soft skills, the top 10 skills were almost all soft.

In other words, the emerging Feeling Economy is set to impact organizations across all industries. We need to get used to AI-HI (human intelligence) teams, letting each do what it is best at. And what humans do best — at least for now — centers around, feeling, empathy, and interpersonal interactions.