A survey from Monster shows there’s a real disconnect between what job seekers think of the current employment market and what recruiters say.

shows there’s a real disconnect between what job seekers think of the current employment market and what recruiters say.

While recruiters regularly report how hard it is to find quality candidates, several thousand job seekers insist it is harder to find a job today that it was last year. What’s more, by a margin approaching three to one, they agreed with the survey statement that, “The job market is saturated with qualified people in my area of expertise.”

They also believed when they took the online survey at the beginning of the year that the number of jobs hadn’t grown in a year; 62 percent thought that. The reality, according to The Conference Board, was that there were almost 600,000 more jobs being advertised in January and February when the survey was conducted.

Why the disconnect?

For one thing, overall confidence was significantly lower six months ago when the economic news was full of fiscal cliffs barely averted and impending sequestration. Another reason could be the nature the employment profile of the survey respondents; only 42 percent of the 6,000 were employed at the time they took the survey.

With recruiters reluctant if not resistant to even talking to the unemployed, it’s certainly likely that the 3,500 respondents not then working were finding it difficult to get a foot in the door. Monster didn’t break down all of the survey into employed and unemployed, but out of the 6,000 respondents, 57 percent identified “Getting an employer or recruiter to contact me” as a major challenge to their job hunting success. Close behind — at 56 percent — was finding a job that matched what they wanted.

That such a large proportion of the survey-takers were out of work was probably to be expected. The unemployed have a powerful motivation to job hunt, and indeed, 90 percent of the respondents — unemployed and those who still had jobs — agreed that looking for work was a full-time job in itself. Of the unemployed respondents, half were out of work for more than six months when they took the survey; 31 percent were unemployed for over a year.

Another telling indication is the education level of the respondents:

- 23 percent had a high school education or less;

- 33 percent had at least some college or an associate’s degree;

- 44 percent were college grads.

The survey doesn’t line up educational attainment with employment status, but it’s not unreasonable to assume that the less schooling the respondents had, the more likely they were to be unemployed. In January, 12 percent of those without a high school degree were unemployed. Compare that to the 3.7 percent unemployment rate for those with at least a bachelor’s degree.

However, what should raise yellow flags for managers and HR professionals was that 42 percent of job searchers who were employed.

However, what should raise yellow flags for managers and HR professionals was that 42 percent of job searchers who were employed.

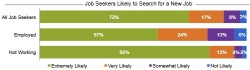

We’ve been hearing for some time that workers are chafing about their jobs. Dissatisfaction runs high, by almost any measure and according to every survey. Monster’s own survey found 57 percent of the employed workers “extremely likely” to search for a new job. Add in those who said they were “very likely” and the 81 percent total isn’t far off what other surveys have found.

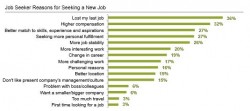

And why do they want to change jobs? Just over a third because they lost their last one; 32 percent for more pay. But then there’s the 27 percent who want more job fulfillment; 20 percent want more interesting work; 17 percent want to be challenged more.

These responses speak to the engagement problem too many employers have and too few address. A survey by the American Management Association found that 61 percent of business leaders see nothing urgent in the potential job changing intentions of their workforce.

Dismissing intentions expressed in a survey is easy when you think how easy it is for a survey taker to declare themselves “likely” or “extremely likely” they’ll be job hunting in the next 12 months. Actually doing it? That can be a totally different matter. Yet, the fact that currently employed workers found their way to Monster says that a sizable percentage are doing more than simply expressing an intention; just going to a job board is an action.

Of course it doesn’t mean all those employed workers who went to Monster in January and February were ready to commit then to a determined job search. But it does tell us that the intentions they express can morph into action by the right combination of factors.

The disconnect I mentioned at the beginning of this article, as well as personal inertia, may be keeping workers from turning their passive job hunt into an active one. But as personal dissatisfaction creeps up the frustration scale, and worker confidence in finding work grows, those with skills in demand, those with the best talents, will convert into active seekers and be the first to be hired away.