In case some of you are wondering who the best is, they are up here on this plaque.

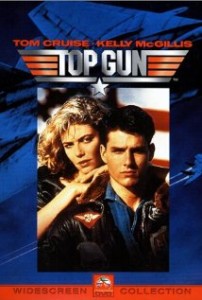

That line from the 1986 film Top Gun — a film about Navy aviators — sums up the surprising problem besetting the Air Force. It can’t retain its fighter pilots. Increasingly, its pilots are remembered with retirement plaques.

That line from the 1986 film Top Gun — a film about Navy aviators — sums up the surprising problem besetting the Air Force. It can’t retain its fighter pilots. Increasingly, its pilots are remembered with retirement plaques.

It wasn’t that long ago that 80 percent of the service’s fighter pilots would re-up after their initial 11 year commitment. Today, the percentage is 65. And unless that improves, the Air Force estimates that its current 200 pilot shortage will grow to 700 in the years ahead.

To combat the problem and get more experienced aviators to stay the Air Force announced a lucrative retention program upping the pay for pilots and offering a bonus worth $225,000 for experienced pilots who sign-on for nine more years.

The Aviator Retention Program has been around since 1989, but it has become an ever-higher priority as the number of departures has accelerated. “Were it not for the program, there would be a greater problem than the one we currently have,” program manager Lt. Col. Kurt Konopatzke told the Los Angeles Times.

Considering it takes no less than two years and $6 million to get an officer (all pilots must be officers) combat ready, retention has become a major issue. (The other services with air units have some retention issues, but none approaches the challenge faced by the Air Force.)

The Air Force cites a number of reasons why its top gunners are leaving: family demands, reduced time flying dictated by budget cuts, reassignment of cockpit flyers to remote drone piloting, and growing demand for airline pilots. Rob Streble, an official with the U.S. Airline Pilots Association, said not only do the airlines pay better, but they offer more family stability.

“The military is difficult on the family with all the moving around,” he told The Times.

An experienced commercial airline pilot can command an annual salary of more than $160,000, though the average for pilots and other cockpit crew is about $130,000. A fighter pilot with a decade of military flying can earn $90,000.

While military life has its unique challenges — frequent reassignments among them – what the Air Force blames for its retention problems may be only the outer layers of a more profound institutional change, not unlike those the private sector has been wrestling with since the start of the recession.

In September 2011 the Air Force gathered its top leaders from around the world for a summit in Washington to discuss the implications of a smaller manned fleet and fewer aviators. As the price of aircraft, including, and maybe even particularly, fighter jets continues to rise, and at the same time the capability of remotely-piloted and self-guided drones improves dramatically, the number of manned craft has grown smaller.

In 2009, a RAND report projected the Air Force would have about 1,000 fighters in 2016; two-thirds fewer than it did in 1989. The inventory may not dip that low, but the reduction has cut training and flight time for experienced aviators. Keeping planes on the ground saves money, but it also means pilots don’t do what pilots are in the service to do and that’s to fly.

The camaraderie and esprit de corps so much on display in Top Gun is being eroded as pilots get assigned to other jobs. This sense of loss of what was is very much evident in a two-year old post on FightPilotUniversity.com. Posted a few months before the Washington meeting, an email purportedly from a senior officer to fighter pilots notes, “The fighter community is faced with an increasing ops tempo, fewer fighters, less flying, more non-flying jobs and an unclear career sight picture.” The email goes on to ask for feedback from the pilot community: “I want to know as much as possible about what’s causing retention to move in the wrong direction.”

The results of that request aren’t on the site, but a poll of readers is. It’s unscientific and may not be representative of the active duty personnel, since the site itself is dominated by retired fighter pilots, However 55 percent blame “too much BS and not enough flying” for the retention problem.

As one of the writers on the site says, “Fighter Pilots, doing the most dangerous and demanding job in the Air Force, are no longer treated as “special.”

The retention program, focused as it is on money, may help. But as so many corporate programs show, money rarely solves the problem.