An IT recruiting watchdog group says some staffing companies are abusing the U.S. visa program, advertising jobs that may not even exist, and limiting applicants to non-citizens.

“The public is led to believe that companies can’t find Americans to fill high-tech jobs when, in fact, they are not searching for Americans — as these ads show,” said Donna Conroy, a founder of Bright Future Jobs and author of “No Americans Need Apply.”

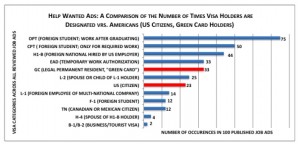

Her report details an analysis of 100 IT ads, posted on tech job board Dice.com, which all include language referencing various visa programs, and which, Conroy said in an interview, are phrased as “code for foreign workers only.”

The Bright Future Jobs analysis of the ads found 37 percent of them made no mention of IT job terms or skills in the ad title. Instead, they contained only references to visa types, says Conroy’s report. “These 37 ads also repeated these USCIS (US Citizenship and Immigration Services) terms in the skills section,” says the report.

The balance of the ads all included visa terms, with many restricting applicants to those with H1-B visas (work visas) or with work permits granted to foreign students attending U.S. colleges and universities.

Remarkably, one ad reproduced in the report, makes no reference to skills at all. Another ad seeks entry-level computer science graduates, telling potential applicants they’ll get help doctoring their resume:

We will provide you the sample resumes with which you need to prepare blueprint of your resume with 5-8yrs of exp, as per current market needs to compete with others and we will assist you further in all aspects while finalizing your resume.

That’s not unusual, says Conroy, who called the recruitment ads a “scam and a fraud. It’s been going on for 20 years, and not only here, but in Australia, the United Kingdom and other places.”

Referred to as body shops, these mostly Indian-owned IT staffing firms recruit in India, promising jobs and training in the U.S. Hopeful candidates pay for the placement — as much as $10,000 Conroy said — and go to work for a staffing firm that arranges their work visas. Contrary to popular belief, few jobs must first be advertised to American citizens.

These firms have their own network, and share candidates during down times. Wikipedia’s body shop entry explains one sort of sharing arrangement.

“Essentially,” says Conroy, “it’s a guarantee (for the workers) of a bright future when they return to India in a couple of years.” Not only is their U.S. experience highly valued by software firms in India, the earning potential of those with that kind of experience significantly increases marital dowries, Conroy explained.

The ins and outs of this global staffing network was detailed in Global “Body Shopping”: An Indian Labor System in the Information Technology Industry, by anthropologist Xiang Biao, a professor at Oxford University.

Although salaries and opportunities have risen sharply in India since the emergence of body shops in the mid-1990s, IT graduates there find so much advantage in gaining overseas experience, that they are willing to pay the fees and even endure often uncomfortable periods of unemployment — with no pay — living in housing that may be owned by the staffing firm.

Besides collecting fees from the candidates, the staffing companies bill out their workers at rates approaching as much as $100 an hour, while paying them far less. Many times, however, the hourly rate is far less than what an employer would have to pay an American IT staffing firm. Consequently, some employers choose not to look too closely at the workers provided by these firms.

Most of the staffing firms involved in these body shop arrangements, Conroy said, are small operators, though her report lists ads by firms with revenues of several million dollars.

Infosys, one of the largest software services and staffing providers with 15,000 workers in the U.S. and revenue of more than $6.8 billion, is under investigation for alleged visa fraud. The firm is also being sued by a former consultant whose allegations of visa fraud prompted the criminal investigation.

Visa fraud takes many forms; the most common is when the holder does work not allowed under their specific visa. In other cases, the staffing company, which is the actual employer of record, fails to comply with the rules under which the visa is granted, claiming the worker is paid a salary large enough to be exempted from them.

Visa fraud takes many forms; the most common is when the holder does work not allowed under their specific visa. In other cases, the staffing company, which is the actual employer of record, fails to comply with the rules under which the visa is granted, claiming the worker is paid a salary large enough to be exempted from them.

Beyond the visa issues are those involving EEOC compliance. Discrimination on the basis of national origin is prohibited under American law. Since only non-Americans would need a visa to work in this country, ads requiring a visa would likely be discriminatory.

The report quotes visa and immigration attorney Michael F. Brown of Peterson, Berk & Cross saying, “If the employer in fact does not hire U.S. citizens as a matter of practice, this could potentially involve the violation of discrimination law for a U.S. citizen job applicant who is bypassed based on his or her national origin.”

How widespread a problem this is, isn’t known, since no agency is specifically charged with monitoring and tabulating all the various visas issued and which are still active. Conroy suggested it is into the tens of thousands.

While Congress may act later this year to tighten up restrictions on work-related visas, Conroy said recruitment sites like Dice “are part of the problem. They don’t enforce their own policies.”

“Until these companies go to EEO-rehab, Dice must step in and remove all job ads that even have a hint of discrimination, “ said Conroy in a press release announcing the report.

Tom Silver, Dice’s SVP, North America, said via email, “Our policy is to remove any ad that violates our terms of use . We proactively search our site daily for discriminatory ads and follow our policy to remove the ad.”

A Dice spokeswoman said, “We’ve addressed 167 job advertisements this year that violated our terms of service.”

Silver noted that, “Visa language in a job advertisement doesn’t amount to discrimination in and of itself, job postings with these terms and others are reviewed on a case by case basis.” And indeed Dice (as well as Monster and CareerBuilder) all have ads that in some cases say applicants with such visas won’t be considered or that the company won’t assist in obtaining them.

Although Bright Future Jobs found 100 allegedly discriminatory ads on the site, Silver explained there is a time lag between finding a potentially discriminatory ad and removing it. However, he added, “We will continue to enforce the terms of use for our site which spells out our position of zero tolerance of discriminatory ads.”